Bigger Isn’t Always Better

The Impact of Fund Size on Private Equity Performance

Since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008, the U.S. private equity (PE) market has expanded dramatically, with funds ranging from small lower middle-market (LMM) vehicles to multibillion-dollar mega-buyout funds. These categories are typically defined by fund size, for example, “small-cap” or lower middle-market PE funds often have less than $1 billion in committed capital, mid-market funds range roughly $1 to $5 billion, and large or mega-cap funds exceed $5 billion. As more mega-cap funds are raised and deployed, investors are questioning the ability of these funds to generate the same relative performance as their smaller PE fund peers. As we continue our expansion into PE, we looked at the performance trends since 2008 across market cap fund sizes. We analyzed why smaller funds may potentially generate superior returns relative to larger funds. We also dove into fund size dynamics and trade-offs to generate data-driven insights, including potential risks investors may face when investing in smaller funds.

Performance Trends by Fund Size

Numerous studies and industry datasets consistently show that smaller private equity (PE) funds have outperformed larger funds since 2008. Recent academic research finds a clear pattern: for every 1% increase in fund size, net IRR declines by about 0.1%.[1] Put simply, larger funds generate slightly lower returns, all else equal.

One explanation is that large funds are forced to pursue larger deals, historically underperforming smaller transactions. This trend is confirmed across multiple sources:

Cambridge Associates reports that small and mid-sized buyout funds have achieved higher net IRRs than mega-funds over several vintages.[2]

McKinsey found that over the last decade, small and mid-cap buyout funds outperformed large-cap funds by up to 4% in IRR.[3]

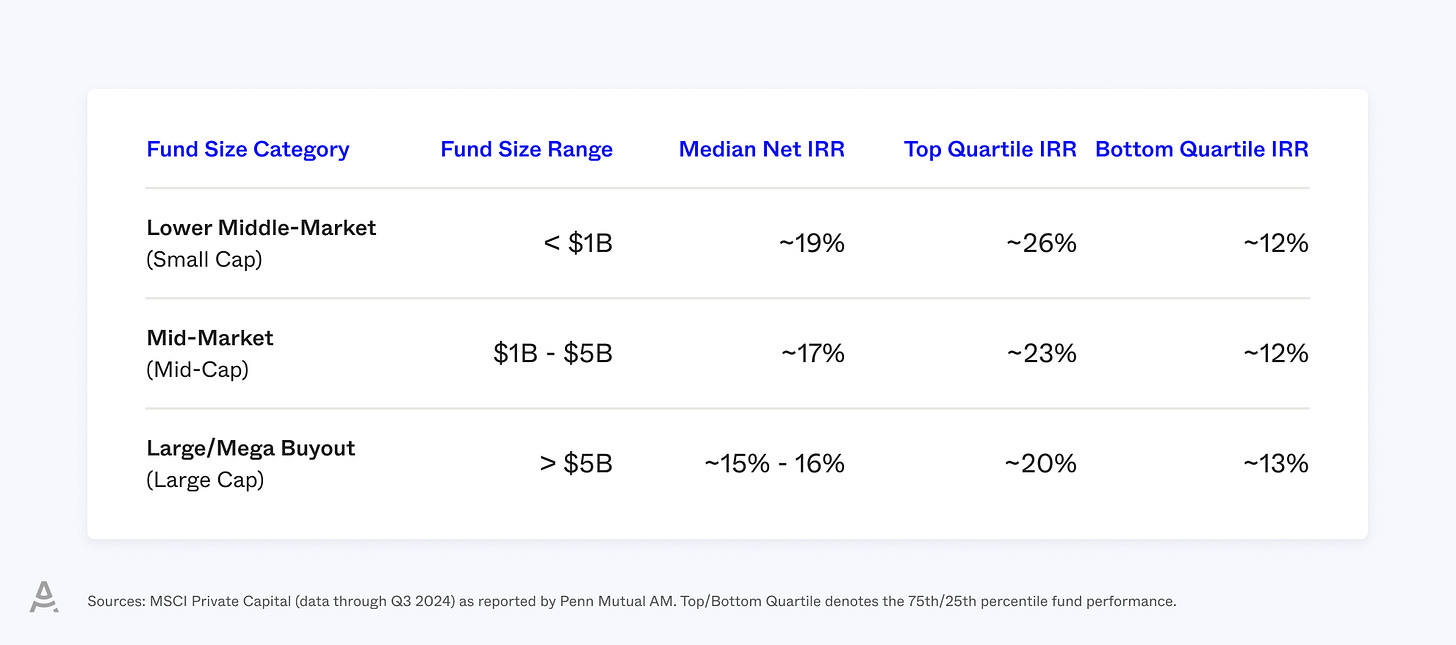

Table 1 (below) illustrates these performance differences by fund size, showing that lower middle-market funds had the highest median and top-quartile IRRs in the post-GFC period. However, it’s important to note that smaller funds also show a wider spread between top and bottom performers, indicating greater variability, or “dispersion,” in outcomes. This higher dispersion among small funds is discussed in more detail later.

Table 1. Net IRR Performance of U.S. Buyout Funds by Fund Size (2010–2020 Vintages)

Beyond IRRs: Why Smaller Funds May Offer a Liquidity Advantage

Cash return metrics, such as Distributions-to-Paid-In (DPI), reveal a compelling edge for smaller private equity funds that often goes underappreciated when focusing solely on IRRs.

A 2025 study from PGIM[4], covering vintage years 2003 to 2021, found that lower middle-market buyout funds consistently achieved higher DPI ratios than their larger counterparts, both in the top half and at the median of performance distributions. This advantage has persisted in more recent vintages (2022 to 2024), with lower mid-market and mid-market funds generating greater liquidity through cash distributions compared to mega-funds.

Faster capital payout can improve an investor’s realized IRR and shorten the duration of the J-curve, underscoring a potential liquidity benefit associated with smaller fund strategies.

More Dispersion, More Opportunity—And More Risk

While average returns may favor smaller funds, performance varies significantly across the distribution. Research from Cambridge Associates[5] found that:

Realized small-cap deals generated an average MOIC of ~2.8x.

Large-cap deals, by comparison, delivered a more modest ~2.4x average.

The small-cap universe also included:

A greater share of outsized winners (5x+ returns)

A higher incidence of losses (returns below 0.5x)

Large-cap deals, in contrast, tended to produce less dispersed outcomes. This pattern reinforces the idea that smaller funds carry a higher-risk, higher-reward profile: while top-performing small funds can far exceed the returns of large funds, underperformers can fall dramatically short.

Why Mega-Fund Returns Cluster Around the Median

A common challenge for mega-funds is the limited supply of sufficiently large deals to absorb their growing capital bases. As one industry newsletter summarized it:

“An abundance of capital in mega-funds chasing a limited set of large deals causes returns to ‘cluster around the median.’”

This crowding effect compresses return dispersion and contribute to a tighter band of outcomes—often closer to industry averages. While this may appeal to investors seeking consistency, it limits the potential for significant outperformance.

Structural and Strategic Advantages of Smaller Private Equity Funds

Lower middle-market (LMM) and mid-market private equity funds have demonstrated notable outperformance relative to mega-funds in recent years. This trend is underpinned by distinct structural advantages and a differentiated strategic approach that enables smaller funds to access unique opportunities, apply more hands-on value creation strategies, and achieve more flexible exits. While large funds prioritize scale and consistency, smaller funds have leaned into focus, specialization, and a segment of the market that remains inefficient and underpenetrated.

Access to Higher-Growth Companies

Smaller funds target companies earlier in their growth trajectory, where revenue and earnings can compound meaningfully through organic and operational expansion. Cambridge Associates notes that nearly 75% of the highest-growth private investments, those with more than 20% annual revenue growth, originated in the small-cap space.[6] These businesses tend to have more fragmented operations, nascent professional structures, and greater responsiveness to hands-on ownership.

This contrasts with large-cap buyouts, which often involve mature businesses already operating at scale with more limited room for step-change growth. In the lower middle market, sponsors can catalyze growth through initiatives like professionalizing management, entering new geographies, and expanding product lines. The opportunity to drive alpha through growth, not just financial engineering, is structurally more accessible at the small end of the market.

Less Competition, More Attractive Entry Valuations

Another critical advantage is the supply-demand mismatch in capital and deal flow. The LMM space encompasses over 100,000 companies across North America, accounting for more than 90% of the private equity addressable universe. Yet over 80% of private equity capital is concentrated in funds greater than $1 billion.[7] This imbalance creates an environment where fewer investors are competing for a larger pool of deals, reducing pricing pressure.

Empirical data reflects this: in 2023, U.S. middle-market buyouts with enterprise values below $1 billion traded at an average of 8.8x EBITDA, while large-cap deals averaged 11.6x.[8] PitchBook data on sub-$500 million EV deals confirms this pattern, with multiples closer to 9x. These valuation gaps provide a broader margin for error and greater potential for multiple expansion upon exit.

Furthermore, the lower end of the market remains less intermediated. Only 18% of deals under $10 million in EBITDA go through broad auctions, according to RCP Advisors. This dynamic allows smaller funds to source deals off-market or through proprietary channels, accessing less competitive, more attractively priced opportunities.

Operational Control and Active Value Creation

Smaller funds typically operate with more concentrated portfolios and deeper engagement at the asset level. Rather than relying on leverage or macroeconomic tailwinds, LMM GPs frequently deploy operational expertise to transform businesses from the inside out.

These efforts may include building out management teams, upgrading back-office systems, streamlining supply chains, or entering new distribution channels. Many target companies are founder- or family-run and are approaching a natural transition point, making them ripe for institutional ownership and strategic scaling.

In contrast, mega-funds often run portfolios of dozens of companies, necessitating a more standardized approach. Their playbooks may emphasize financial structuring, bolt-on acquisitions, and cost optimization, but they tend to have less capacity for high-touch transformation. Cambridge Associates highlights the opportunity for multiple expansion when companies grow from small- to mid- or large-cap scale—value that small funds are structurally positioned to capture.

Broader and More Flexible Exit Paths

Smaller portfolio companies also benefit from more diverse exit options. A business valued between $50 million and $300 million can be an attractive target for a wide range of acquirers: strategic buyers seeking growth, larger PE funds moving upstream, or even the public markets. This flexibility increases the probability of a timely and profitable realization.

Large-cap buyouts, by comparison, often require exits to other mega-funds or large corporates, limiting options and creating liquidity bottlenecks. Public markets are a viable path for large-cap exits, but IPO windows can be sporadic. In the wake of COVID and amid heightened macro uncertainty, large exits have slowed while LMM sponsors continued to return capital through strategic and sponsor-to-sponsor deals.

Incentive Alignment and Cultural Discipline

Fund size also shapes GP behavior. Managers of mega-funds collect substantial management fees (i.e., 2% on a $10 billion fund translates to $200 million annually) independent of performance. This structure can dampen the marginal impact of fund returns on the GP’s own economics.

In contrast, smaller funds rely more heavily on carried interest to drive compensation. With limited base fees, GPs are directly incentivized to create value and deliver strong returns. This alignment reinforces a performance-driven culture and often translates into greater effort and discipline in deployment and execution.

Preqin research shows that emerging managers, which are typically smaller and younger, have outperformed established firms by roughly 3% in net IRR.[9] While the tradeoff is less experience and higher manager selection risk, the upside can be meaningful. As the CIO of StepStone recently noted, “now is the time to lean into small buyouts,” citing structural advantages like less competition, lower entry valuations, and greater operational value creation potential.

The case for smaller funds rests on more than just anecdote—it is supported by structural realities, valuation data, performance dispersion, and exit flexibility. Lower middle-market and mid-market funds operate in a segment where private equity remains less efficient, competition is lower, and the tools for value creation are more potent. For investors with access to top-tier small-cap GPs, this segment continues to offer strong prospects for excess returns in a market where alpha is becoming increasingly difficult to source at scale.

Understanding the Risks: The Other Side of the Small-Fund Coin

While the return potential of lower middle-market (LMM) private equity is compelling, investors must also weigh the distinct risks that come with smaller funds. Higher performance dispersion, constrained scalability, and the need for sharp manager selection are central considerations that differentiate this segment from its mega-fund peers.

Illiquidity and Allocation Constraints

Private equity is inherently illiquid, but small funds can amplify this challenge. Capital is typically committed for 10 or more years, and selling stakes in niche small funds on the secondary market can be more difficult than exiting larger, more widely held funds. Furthermore, top-performing LMM funds are frequently oversubscribed and may offer limited access to new LPs, similar to the access constraints seen in high-performing venture funds. Investors looking to deploy meaningful capital face a scale mismatch; large institutions such as pensions or endowments would need to invest in dozens of small funds to reach target allocations—an administratively intensive task. Securing an allocation in the right small fund often demands both persistence and deep due diligence, especially when capacity is tight and fundraising windows are short.

Execution and Operational Risk

Smaller portfolio companies tend to come with higher execution risk. These businesses are often founder-led, under-resourced, and lack robust financial, operational, or governance infrastructure. This makes them more vulnerable to market disruptions or management missteps. In these deals, much of the value creation hinges on the GP’s ability to professionalize and scale the business—an inherently high-stakes endeavor. Additionally, many LMM funds are run by emerging managers with limited track records or internal resources, amplifying the dependency on execution skill. These dynamics contribute to the wider return dispersion seen in small-cap buyouts. As highlighted earlier, while small funds may produce some of the industry’s biggest winners, they also account for a disproportionate number of underperformers. Outcomes are more idiosyncratic, and only a subset of GPs consistently generates top-quartile returns.

Portfolio Concentration and Volatility

The smaller scale of LMM funds means they typically hold fewer companies, which results in greater concentration risk. A $300 million fund might invest in just 8 to 10 companies, compared to 30 or more in a $10 billion fund. This lack of diversification magnifies both upside and downside potential. A single write-off can meaningfully drag down fund performance, while a single 5x winner can lift overall returns substantially. This dynamic can make performance more volatile than in large, diversified portfolios, and demands thoughtful sizing of LP commitments. Some investors mitigate this by building portfolios of multiple small funds or by diversifying across strategies and sectors. However, concentration risk remains a defining feature—and a double-edged sword—of smaller fund investing.

The Importance of Manager Selection

Manager selection is especially critical in the lower middle market. Unlike large-cap buyouts, where performance is more tightly clustered around the median, small-fund outcomes are far more dispersed. Simply investing in the category does not guarantee outperformance. The difference between a top-quartile and bottom-quartile manager in this space can be stark. As a result, deep due diligence on strategy, sourcing edge, team experience, and operational capabilities is essential. Research from Penn Mutual and others underscores that manager selection—not asset class exposure alone—drives returns in this segment. Many LPs reduce the burden of sourcing and evaluation by leaning on consultants, fund-of-funds, or returning to proven GPs. Without rigorous filtering, the statistical promise of the small-cap category may never be realized in actual portfolio results.

Resilience and Risk Mitigation in Downturns

Despite these risks, certain characteristics of small-fund portfolios can enhance resilience in market downturns. While small businesses are less established, they typically carry lower leverage than their large-cap counterparts. During the Global Financial Crisis, small-buyout valuations declined by just 12.6% from peak, compared to over 33% for large and mega-buyout funds.[10] The combination of lower debt, fewer mark-to-market pressures, and more conservative accounting can reduce volatility during stressed environments. That said, small companies remain vulnerable to shocks, and navigating recessions still requires capable GPs with flexible investment timelines. When managed well, these structural traits can offer downside protection even as the upside potential remains intact.

Investing in lower middle-market private equity demands a higher tolerance for variability and a more hands-on approach to manager selection. Illiquidity, execution risk, and concentration are real and meaningful challenges. Yet, with rigorous diligence and the right GP partnerships, these risks can be managed—or even turned into advantages. Small funds require more effort and discipline from LPs, but for those able to access quality managers and build a diversified small-fund portfolio, the reward potential remains one of the most compelling in private equity.

Conclusion – Why Fund Size Still Matters

Over the last 15 years, particularly since the Global Financial Crisis, lower middle-market and mid-market private equity funds in the U.S. have consistently outperformed their larger peers. This performance gap supports the view that, at least on average, smaller really can be better in private equity. Smaller fund sizes have allowed GPs to operate in less efficient corners of the market—acquiring companies at lower entry multiples, accelerating growth through operational improvements, and capturing outsized value at exit. A wide range of studies, from academic research to industry benchmarks, reinforces the inverse relationship between fund size and performance. The drivers of this dynamic are clear: smaller funds gain access to higher-growth businesses, face less competitive deal processes, and benefit from stronger alignment and execution agility. Yet the opportunity comes with meaningful tradeoffs. Smaller funds also bring greater variability in outcomes, heightened concentration risk, and a heavier reliance on GP quality. In our experience, sophisticated investors are navigating this landscape by adopting a barbell strategy, pairing select smaller funds for alpha generation with larger funds for scale and consistency.

At Allocate, we don’t see fund size as a binary choice but rather as a portfolio construction lever. A well-designed private equity program can and should incorporate both ends of the spectrum. For investors willing to do the work, such as diligencing managers, securing allocations, and accepting some illiquidity and volatility, the lower middle market offers a compelling source of differentiated returns. The post-2008 era has made clear that smaller funds, when thoughtfully selected, can be a powerful engine for value creation. Fund size continues to matter in private equity.

[1] National Bureau of Economic Research, “Does Fund Size Affect Private Equity Performance? Evidence from Donation Inflows to Private Universities”, Bhardwaj, A., et al, March 2025

[2] Cambridge Associates, Global Private Equity & Venture Capital Index and Selected Benchmark Statistics, Q4 2022.

[3] McKinsey & Company, Global Private Markets Review 2023, March 2023.

[4] PGIM, “Unlocking Liquidity: The Distribution Edge of Lower Mid-Market Private Equity”, Accessed 24 June 2025

[5] Cambridge Associates, “US Private Equity Looking Back, Looking Forward: Ten Years of CA Operating Metrics”, Auerbach, A., et al, November 2022

[6] Cambridge Associates, “US Private Equity Looking Back, Looking Forward: Ten Years of CA Operating Metrics”, Auerbach, A., et al, November 2022

[7] RCP Advisors, “The Case for Small Buyouts”, Accessed 24 June 2025

[8] PineBridge, “Private Equity Dry Powder Is Still Elevated. Should Investors be Worried?”, Chen, C., & Pollack, J., 30 July 2024

[9] The Buyside Journal, “The Impact of Fund Size on Private Equity Performance: Navigating the Trade-offs Between Small and Large Funds”, 25 September 2025

[10] StepStone Group, Fight the Urge (to cut back on small buyouts), January 2023

MARKET COMMENTARY

Any opinions, assumptions, assessments, statements or the like (collectively, “Statementsˮ) regarding market condition, future events or which are forward-looking, including Statements about investment processes, investment objectives, goals or risk management techniques, constitute only the subjective views, beliefs, outlooks, forecasts, projections, estimations or intentions of Allocate Management, should not be relied on, are subject to change due to a variety of factors, including fluctuating market conditions and economic factors, and involve inherent risks and uncertainties, both general and specific, many of which cannot be predicted or quantified and are beyond Allocateʼs control. Allocate undertakes no responsibility or obligation to revise or update such Statements. Statements expressed herein may not be shared by all personnel of Allocate.